Pawikan Patrol Designer Spotlight – Mykey Cuento

Mykey Cuneto combines boardgames, education and the environment.

It is summertime in the Philippines! Mykey Cuento’s travel friendly game – Pawikan Patrol, is all about the environment and the web of life (and death) surrounding the sea turtle, known locally as the pawikan. The game is perfect for those sessions on your next beach trip or out of town jaunt.

We interview Mykey to learn more about the designer, his philosophies and the game.

Ungeek: Hello! Can you tell us a little about yourself? How did you get started into boardgame design? What do you do outside of boardgame design, if anything?

Mykey: My real name is Marc Reuben Cuento, but I was nicknamed Mykey by my Mama who’s a big fan of Mickey Mouse, and has the same birthday as me. She’s also indirectly responsible for me becoming a game designer. From when I was a toddler to preschool, she raised me on LEGOs, Family Computer, and Gameboy. In my preadolescence, this was around 1997, she bought me a pack of Visions from Magic: The Gathering, thinking they were collectible art cards; 27 years later, I still play Magic.

That one pack of cards changed everything for me; it piqued my interest, and Mama was very supportive, so we inquired where else to get Magic: The Gathering, and it inevitably led me to the hobby stores like Nova Fontana where I was first exposed to Dungeons & Dragons literature. Seeing them for the first time, the cover art immediately leapt out at me. I didn’t know what I was looking at, but I was instinctively drawn to the opened copies of D&D books, and reading them, I immediately understood: you can totally play a complex game on the tabletop, without electronics, just paper, pencil, and dice. Even if I had no one to play with, I designed dungeons during class time, generated characters over recess, and played out these adventures on index cards when I got home. During lunchtime, we played Magic in secret, when the teachers weren’t around, and making decks was all I could think about. Without my realizing it, I had already begun designing.

Decades later, summer of 2018, while walking along the beach in Morong, Bataan, a stray thought crossed my mind. I was there making final arrangements for an upcoming sea turtle conservation trip, and under the noontime sun, I decided to take a stroll, picking up trash along the way. Believe it or not, tabletop games are a small, albeit meaningful, part of my life; back then, I was a teacher, traveler, and writer; when I wasn’t teaching, I was organizing tours on the side to raise awareness for the environment and local culture, while also writing for in-flight magazines (I would later get into children’s storybook writing). Busy as I was, that small part of me found a way to insert itself, whispering:

“How about you make a game your students can play and your co-teachers can use to teach about the environment?”

I paused, then my grip on the waste bag tightened. I stared at the sand for a few moments and then to the open sea. Then, it happened: the rules for Pawikan Patrol began writing itself in my mind, turning everything I saw and did into game mechanics. I thought I was having a heatstroke because I got dizzy, so I headed back and began gathering my thoughts. During the drive home, I couldn’t stop thinking about the game; I was already visualizing how it played, what actions players could take, and what medium it would be. Cards. It would have to be cards. The player actions and character cards would mirror their real-life counterparts. It should play fast, fitting inside the 15-minute allocation for activities teachers had in class. It should be small, so that it would be easy to print for multiple groups of students, and take up as little space as possible.

Back then, I was only thinking of my class and my colleagues at work. I never imagined it would go beyond that.

Mykey, back in Morong, Bataan, where Pawikan Patrol was conceived

U: How many games have you designed? Have you published games locally and internationally? What are your main inspirations when you design games?

M: I have designed and successfully published a total of five games, but only one of them is actually commercially available, Pawikan Patrol, first as an independent artist, then later as part of Larong Atin under Ludus Distributors. My game is sold in different Neutral Grounds branches all over the Philippines. I have four other games with different non-profit organizations such as USAID in partnership with BFAR, Save the Children Philippines, YGOAL, and Share-An-Opportunity Philippines; these are what I call client games, games that were made specifically to meet the needs of an organization, particularly in advocacy or training. All of my games have a social awareness angle to it, from protecting our maritime resources in the West Philippine Sea, Disaster Risk Reduction and Management, voter’s education, and inclusive practices. They are typically not available for purchase, but can be made available to interested parties by contacting these organizations.

Pawikan Patrol in Neutral Grounds

All my games require me to properly immerse in the experience I am trying to emulate on the tabletop, which means reading up on literature related to the work these organizations do and actually doing site visits for some field experience. One of these organizations even flew me to Palawan so I can work with professionals.

U: What are specific challenges to being a local game designer and publishing and selling games in the Philippine market? How did you overcome these?

M: By my estimation, based only from membership numbers of local Facebook groups which have several overlaps, not even 1% of our population are exposed to modern tabletop games. Chess is the most popular, obviously, but I have been to places in the Philippines where they haven’t even heard of Monopoly or UNO, so the concept of tabletop gaming as a form of entertainment goes over their heads. There are two contrasting perceptions of tabletop games that you’ll see when you’re out there: either they’re “only for smart people” or “they’re just toys”.

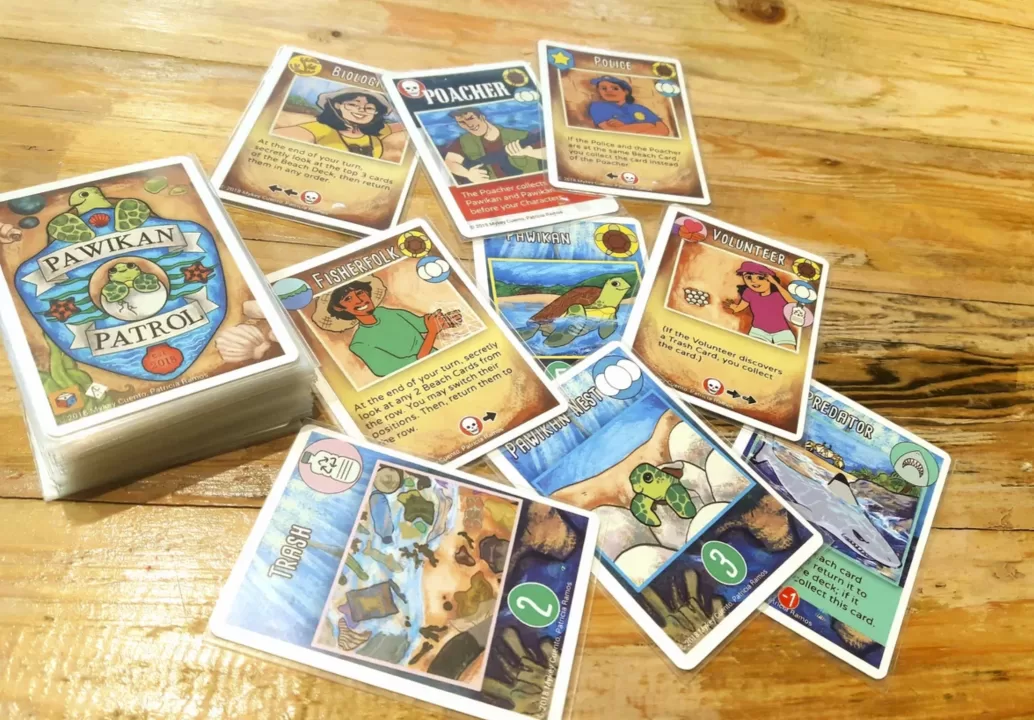

Another obstacle is cost. We’re a poor country, the thought of spending your hard-earned money on pieces of cardboard and plastic is outrageous for many people. Pawikan Patrol, less than $10 at the time of this interview, is still a big ask for most Filipinos, but it has the advantage of having really great art courtesy of Patricia Ramos that catches the attention of kids and has an educational angle. It’s small and compact, at 42 cards, the setup and teardown is quick, it plays in 15-20 minutes including the teach, while also being lesson-friendly, meaning you can insert concepts and takeaways even as you play. It checks all the boxes in terms of being a justified purchase, especially with schools. These days, I do very little marketing for it, as word of mouth over the past five years has taken the game to places I never imagined it would reach, and I would receive inquiries about it almost on a weekly basis, either to ask where to buy, or if I can give a talk about it.

U: Most people get their gaming fix through mobile games these days. How would you try to convince people to try out boardgames? What advantages does it have over playing mobile or video games?

M: Mobile games, quite frankly, are the future. Even card games have moved to that medium and it sells, just look at Marvel Snap. It is inevitable that future generations will keep on being drawn to it by sheer cultural osmosis, especially because of their peers at school. Having said that, schools play a massive role in promoting tabletop analog gaming culture. By making tabletop games an essential analog tool in learning to complement their digital tools, young people become immediately exposed to the medium, and they realize that there are other forms of entertainment available to them, which in turn leads them to tell their parents about it.

Tabletop gaming of course has the obvious advantage of being able to play without plugging in, and encourages face-to-face interactions that remote gaming can’t yet approximate.. There is also the tactile aspect of tabletop gaming that no digital form can emulate, even with shock controllers or VR, being able to physically touch components, look at them, ponder the artwork, etc. That can’t be beat yet. Keyword is “yet” and I would be a fool to not acknowledge a possible future where digital entertainment will eventually be able to bring these experiences to our homes, remotely connecting us. That future hasn’t come yet, however, so in the meantime, we have this to enjoy and cherish. To be able to hold our games and see the person you’re playing with in front of you, with no monitor to filter us, feels just so human.

U: You do custom made, commissioned designs for corporations and government agencies correct? How does it differ from the usual mass market game design?

M: I’ve already spoken a bit about this, but what I can add is that when designing for non-profit and government organizations, you really have to put yourself in their shoes as implementers of a program, but most importantly, look at the design from the lens of their stakeholders, the people they are serving who stand the benefit the most from playing the game. What’s tricky about educational game design is that more often than not, the fun must take a backseat to the learning; it’s a very delicate balance. Speaking of balance, because you’re working under very intense time pressure to deliver, there is little time to balance the game to the standard that the core tabletop audience would be satisfied with; not that it’s actually necessary. In fact, a certain amount of imbalance is needed to ensure that a specific experience or outcome is communicated to the players. Again, the learning must take priority over our typical concept of “fun”. The fun isn’t in being able to min-max the game or have all the possibilities work out; it’s being able to tell a story where the audience can actually participate firsthand. It’s not about commercial viability, but context appropriateness and educational value.

One of Mykey’s client game playtest kits

U: Can you give us a summary of how Pawikan Patrol plays?

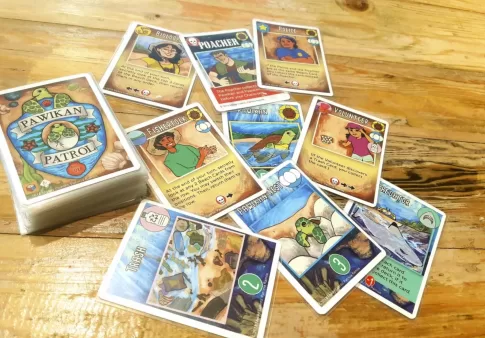

M: In Pawikan Patrol, players score points by rescuing turtle cards and egg cards from the beach before the Poacher, a non-player character, gets them! Helping the players are the Pawikan Patrol, character cards who represent different sectors of society that must work together for marine wildlife conservation. Each character has special abilities that can tell players the location of turtles and eggs or temporarily stop the Poacher. During a player’s turn, they choose an available character, deploy it to a location on the beach, then the Poacher responds depending on the character card you played. The cards at each location visited by the character and the Poacher are revealed, and you check to see whether they are able to collect it based on the icons they have. The game can end in two ways; either when the deck runs out of cards, at which point the player with the most number of points wins, or the Poacher is able to capture six (or eight) cards, resulting in a loss for all players.

The vibrant, kid friendly art of Pawikan Patrol

U: What is your target audience for Pawikan Patrol? Has it been used as an educational tool?

M: When I first conceived of Pawikan Patrol, you’ll remember I was walking along the beach, I was thinking about my students from Grade 4 to Grade 6, the levels I taught in. They were my original intended audience. But during the playtesting phase, I tried teaching the game to increasingly younger groups and realized that it can actually be played by Grade 1 students with some assistance from teachers. Then in 2021, the unthinkable happened: I was invited to an online preschool class at Miriam College Child Study Center, and we played a digital playtest version of the game–and it worked! This would happen again but face-to-face in 2023 and 2024, same school, same age group!

I’m proud to say that Pawikan Patrol has succeeded at being an educational tool. A couple of schools, from private to public, have reached out and adopted the game, adding it to their library, such as UPIS, Miriam CSC, Philippine Science High School, Culiat High School, among others. Some non-profit organizations like Danjugan Island Volunteers in Negros Occidental and YGOAL have even gone so far as to use it as an activity in their training workshops for adults. Parents over the years have gotten in touch as well, telling me how the game rekindled family interaction in their homes by bringing them back to the tabletop.

The game as an educational tool even for young kids

U: What kind of reception did you get on the game (Pawikan Patrol)? Were there any suggestions or feedback that you may adapt to possible expansions or versions?

M: Initial reception for Pawikan Patrol from the local core tabletop gaming community was mixed, which was understandable. Most of the negative reactions came from those who saw the game as being too easy or simple for their taste, while most of the positive reactions came from those who saw Pawikan Patrol’s intended purpose and deliberate design philosophy, a trait shared by many games in the Larong Atin brand. Despite that, it was still heartwarming when I went to a tabletop community Christmas Party, during the Kris Kringle, TWO copies of Pawikan Patrol were given–and neither one came from me! It was hilarious because I was in actual danger of receiving my own game, and it seemed like very few people present knew that the designer was in attendance. Getting featured on short televised segments in ABS-CBN and GMA 7, as well as an article on Inquirer, went a long way in helping Pawikan Patrol reach a wider audience in 2019, as well as boosting its popularity a bit within the local community.

There were several comments and suggestions about the game, but we were really only able to address one of them, the improved Solo/Cooperative Mode which was made into a downloadable PDF with new art from Patricia Ramos. We had other potential expansions planned out, but remember, the game officially hit the market in 2019, so…we all know what happened the following year. The pandemic derailed any plans we had to update the game, but it was still a mixed blessing, because during lockdown, the game saw a spike in sales due to people being stuck at home. During a period when everybody had all the time in the world to play video games, they went back to tabletop gaming as a way to bond.

Compact enough to virtually bring anywhere

Now it’s 2024, and we’re mostly back to our regular programming. Since 2023, I’ve been busy prototyping lots of game designs, including some zines that I will officially launch this year. It’s also been five years since Pawikan Patrol hit game store shelves all over the country, which means we’re almost at the end of its current print run. In that time, we noticed some gameplay elements that could be improved, quality of life changes that would deliver a better experience. There are no promises yet, but we might be looking at a revised edition soon. Pawikan Patrol has become an evergreen title, and it’s still flipping its flippers, so there’s still a lot of ocean left to swim.

U: As an educator and boardgame designer, what would be your message to aspiring Filipino game designers?

M: Don’t do it for money. Don’t do it for fame. Do it because you love the art of game design. Go out there in the world, see as much of it as you can, and get to know different people, because all of those experiences will inspire you to design games that will resonate with the right audience.